About the Map

Contents

Introduction: The Story of Peter Mundy

A sailor from the age of 14, and the son of a Cornish pilchard merchant, Peter Mundy (fl.1600-1667) belonged to itinerant communities driven by the need to find innovative ways of stretching limited resources. The pilchard fisheries in Cornwall declined rapidly over the sixteenth century, and Mundy found employment as a factor with the East India Company. He travelled to Istanbul, China, Poland, Russia, the Arctic and India, and recorded his travels in a unique manner in his manuscript narrative Itinerarium Mundii (MS Rawlinson A.315, Bodleian Library, Oxford). He prefaced his journeys with printed copies of contemporary maps of the world by the Dutch cartographer and print-maker Hendrik Hondius (1573-1650), on which Mundy marked his own routes. His descriptions of places, people, monuments, and happenings then followed, interspersed with his own sketches of scenes. This immediacy, or sense of composing on the move, while his emotional responses to what he witnessed were still forming, is lost in the standard printed edition of Mundy’s Travels (ed. Sir Richard Carnac Temple, Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, 1907-36). Temple’s edition is meticulous in its reproduction and annotation of the written text. But the manuscript - with its self-conscious presentation of travel, its re-use of the Hondius maps, pasted insertion of Mundy’s sketches at particular narrative moments, and later corrections by the author - provides the reader with a different experience of the journeys.

Gujarat Famine, 1630-1632

Our digital map recreates a specific section of Mundy’s narrative of travel in India, where he describes the most serious crisis he witnessed there. The Gujarat famine began with a drought in 1630, attacks on crops by mice and locusts in the following year, and then excessive rain. Famine and water-borne diseases created high mortality: 3 million died in 1631. People migrated towards less affected areas, many died on the way, and dead bodies blocked the roads. Both Persian and European sources tell the story of this famine, with a subverted cornucopoeia of grotesque consumption patterns: cattle-hide was eaten, dead men’s bones were ground with flour, cannibalism was frequent, and people fed on corpses. Carts belonging to banjaras (carriers) transporting grain from the more productive regions of Malwa were intercepted and supplies diverted to feed Shah Jahan’s royal army in Burhanpur, who were fighting territorial wars in the Deccan (southern) provinces. The pre-famine price of wheat was 1 mahmudi per man; in 1631 it had risen to 16. Imperial charitable practices of opening free kitchens and offering land revenue remission had limited effect. Gujarat was one of the main production centres for calico cloth and this trade was badly affected by the death and migration of weavers.

“Famine Chorography”

The aim of this map is to represent not just the route of the journey but also Mundy’s growing understanding of place, space, and people, and his changing emotional responses in the course of his travel. EIC factors like Mundy were aware of fundamental challenges to traditional, seemingly stable conceptions of place posed by vagrancy and/or migration for subsistence or improvement, and the operations of markets and trades. Travel within and beyond national boundaries created abstract spaces of networks shaped by processes of mobility and exchange. For this reason, Mundy’s understanding of place and travel is distinct from that of the Mughal imperial chronicles The Padshahnamas of Shah Jahan’s reign, which also describe the Gujarat famine. Since Mundy’s representation itself occurred in a state of mobility, it was informed by direct, immediate, fluctuating experiences of dearth and plenty, later revised and organised. He constructed what may be termed “famine chorography”: a dynamic type of spatial representation categorising places as a locus of plenty or want. We use the term chorography in the Renaissance sense of written description of regions, often combined with visual elements, including maps, and considered distinct from chronicle history in its prioritising of place rather than time. Mundy’s description of travel through affected areas during the Gujarat famine contained elements common to British domestic travel writing, which utilised and modified chorographic traditions. Places of fluctuating plenty or want were identified along or near routes with an established political or economic significance. The function of the route and itinerary could be pre-defined by traditional, national, or imperial conceptions of space, which the famine chorography of literature representing mobility from below might question or challenge.

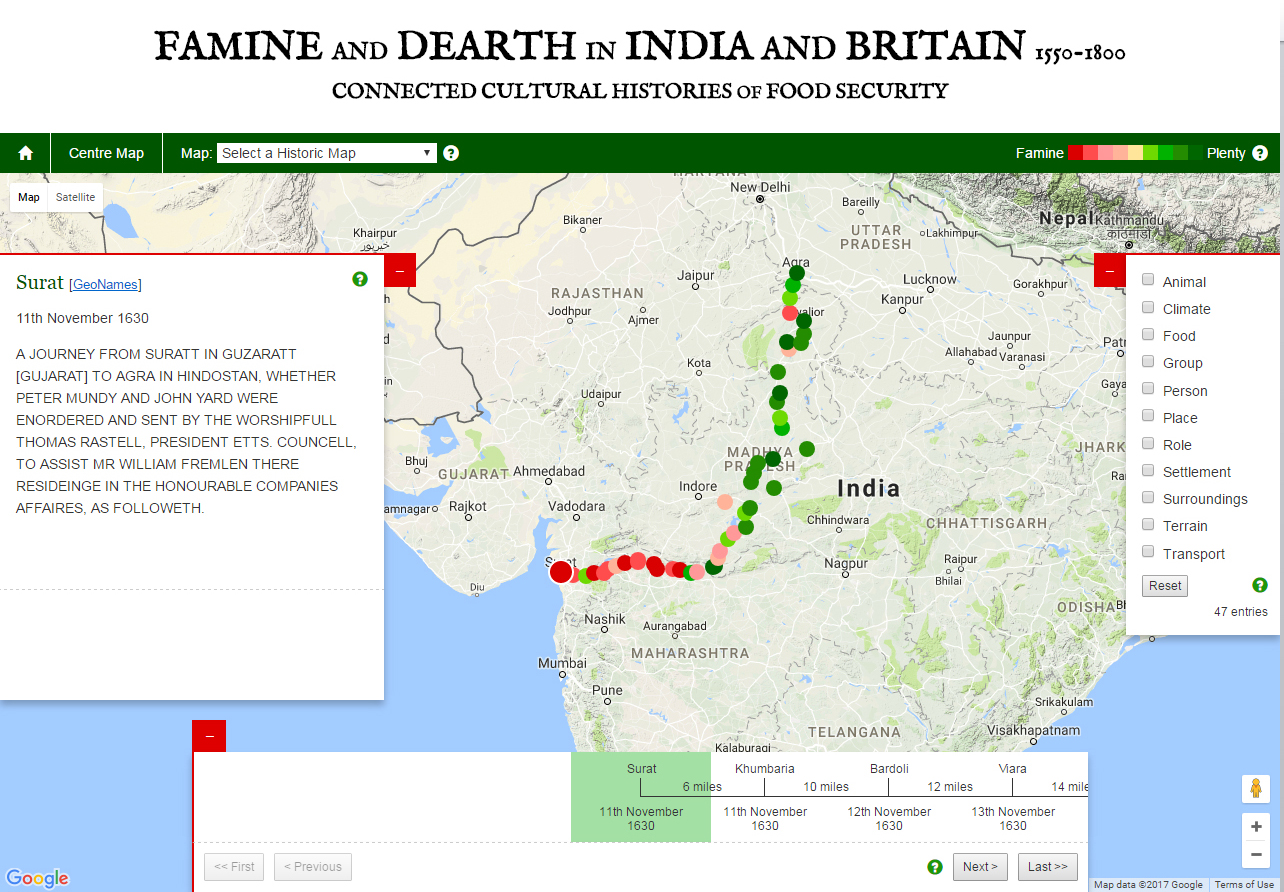

Digitally Mapping Famine Chorographies

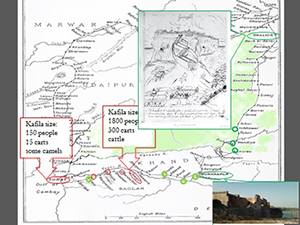

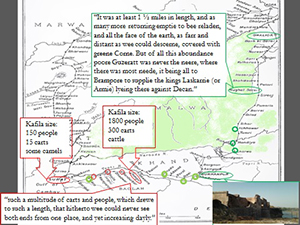

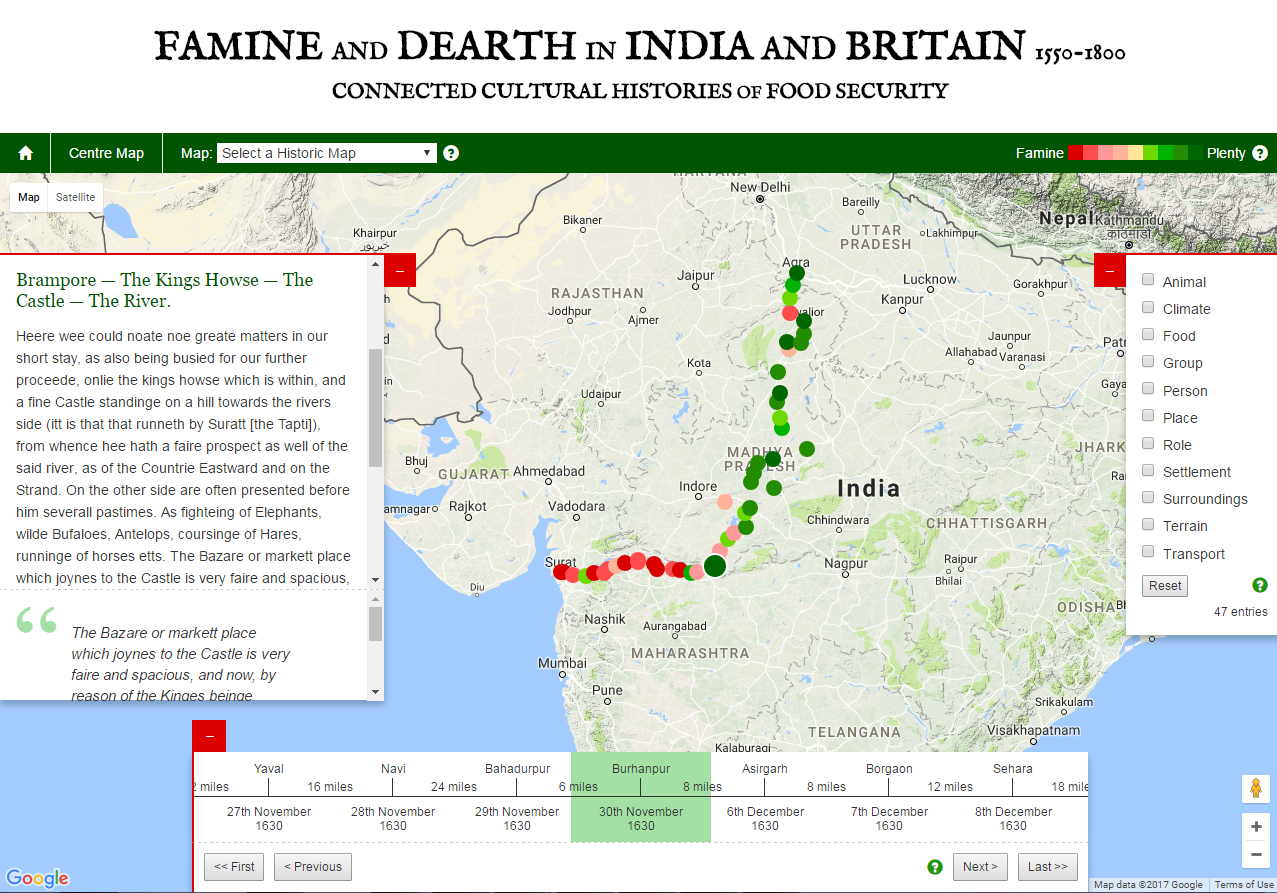

Our digital mapping process has sought ways to visually represent the literary and historical concept of famine chorography, summarised above. Our map-making journey began with the PI’s workshop presentation which proposed the notion of “famine chorography”, using a series of simple maps of Mundy’s journey created with PowerPoint animations.

These were transformed by the Digital Humanities team at Exeter into an interactive digital map to represent Mundy’s emotional reactions to the conditions of plenty or dearth he encountered. His response to each place was measured on a scale of plenty to famine, green to red, and the journey was tracked on a monthly timeline.

Every detail in the text, from the traveller’s reactions and expressions to his registration of facts and observations, was itemised before we determined where a particular place named in the journey could be located on the famine-plenty scale. Using both historical and modern maps, we then identified (as closely as GeoNames would permit!) the current physical location of every place named by Mundy on his route from Surat to Agra. As Mundy’s account gives precise measures of time and distance between places, this was used to construct the timeline to which locations on the map could be linked.

The details of the topography, conditions, and Mundy’s own reactions can thus be simultaneously followed by reading the textual description (searchable by the categories which appear on the right hand column) which alters as the user works through each point in time or place during the journey. The map demonstrates, both visually and textually, how the condition of mobility drove Mundy’s understanding of place, space, and communities of people with whom he shared the experience of shortage. We have tried to capture the volatile and formative spirit of the manuscript text, especially.

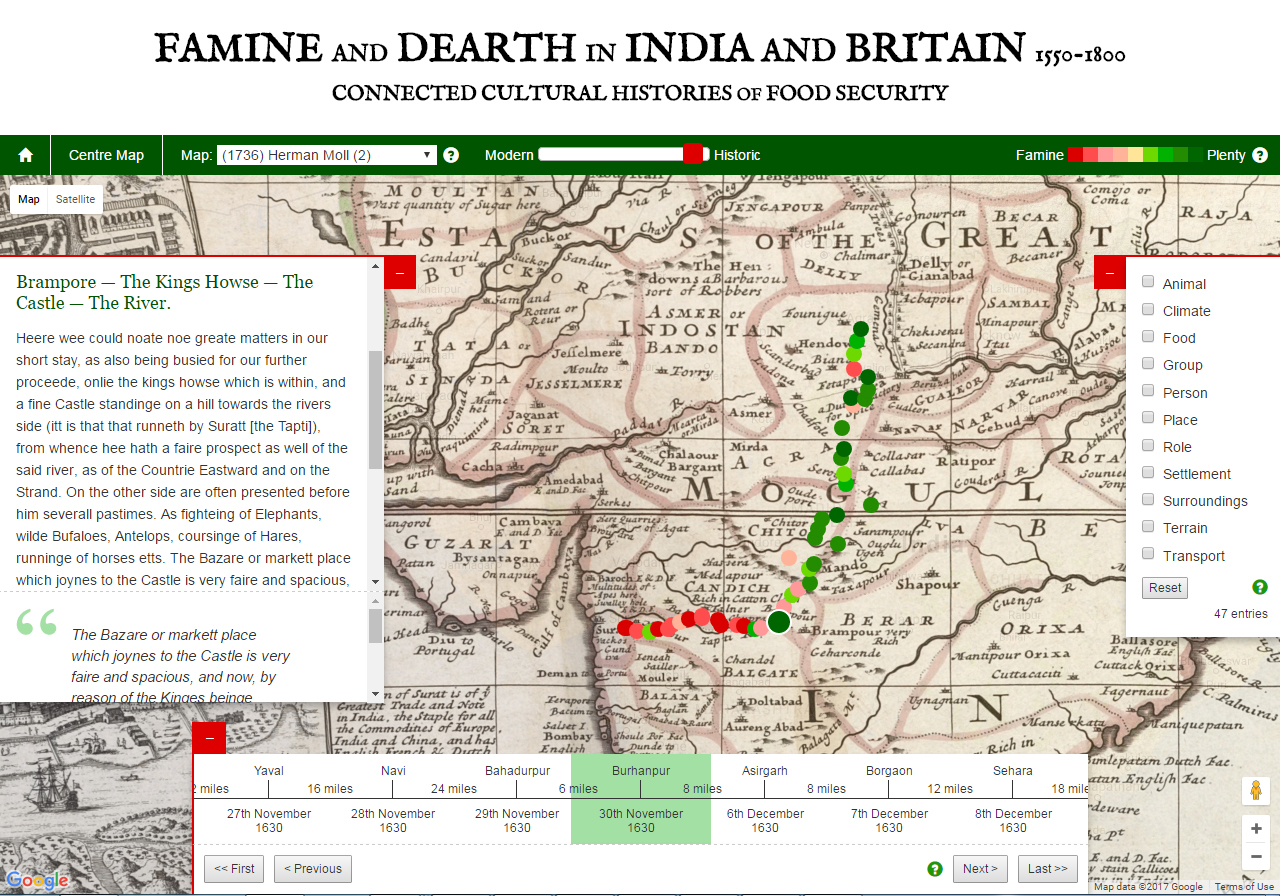

Topographical perceptions and cartographic principles of Mundy’s times were rather different from our modern day observations. We thus added the option for users to experiment with different overlays, so that Mundy’s journey can be seen against a range of famous maps of India, from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. The purpose is to convey the dynamism and amorphous nature of famine chorographies, which can alter in subtle ways over time.

With this map, we hope to have created a basic template for understanding and representing famine chorography in other texts. There are numerous travel narratives relating to India and other parts of the world to which this application could be extended. There are also other kinds of narratives, such as chronicle histories, safarnamas, geographical treatises, or poetry (some of which are part of this database) that could serve to test this template, and refine it. We aim to do so in a future project.

Richard Holding

Ayesha Mukherjee

Hannah Petrie

Gary Stringer

Charlotte Tupman

Technical details

The following data is used to populate the map and is extracted from the TEI markup and the GeoNames service:

- placename

- date of visit (ISO 8601 format)

- distance (from previous location)

- content of journal entry

- quote (highlighting conditions)

- filters (topics mentioned)

- scale (famine to plenty)

- GeoNames id

- latitude

- longitude

The data is stored in JSON format and applied to the map via the Google Maps API. Locations are derived from GeoNames data, and markers are colour coded in accordance with their score on the famine to plenty scale. Navigation buttons allow users to cycle through the text, in sync with the timeline and locations plotted on the map. Filters are taken from the TEI markup and highlight occurrences of particular topics within the text. Overlays were created by Georeferencing and tiling images of maps using MapTiler.

Map overlays

(1736) Herman Moll (1)

Source: India Proper or the Empire of the Mogul. Agreeable to modern history. By H. Moll Geographer. Printed and sold by T. Bowles next ye Chapter House in St. Pauls Church yard, & I. Bowles at ye Black Horse in Cornhill, 1736?

(1736) Herman Moll (2)

Source: A map of the East-Indies and the adjacent countries; with the settlements, factories and territories explaining what belongs to England, Spain, France, Holland, Denmark, Portugal &c.

(1768) Thomas Jeffreys

Source: The East Indies, with the roads. Northern section. By Thomas Jefferys, Geographer to the King. MDCCLXVIII. The second edition. London, published according to Act of Parliament, 30th Apr. 1768 by Robt. Sayer, no. 53 in Fleet Street.

(1771) Rigobert Bonne

Source: Carte hydro-geo-graphique des Indes Orientales en deca et au dela du Gange avec leur archipel. Dressee et assujettie aux observations astronomiques, par M. Bonne, Hydrographe du Roi. A Paris, Chez Lattre, Graveur, ord. de M. Le Dauphin, rue S. Jacq. a la Ville de Bordeaux. Avec priv. du Roi. 1771). Indes Iere feuille.

(1796) Mathew Carey

Source: An Accurate Map of Hindostan or India, from the best Authorities. J.T. Scott Sculp. Engraved for Carey's American Edition of Guthrie's Geography improved.

(1800) William Faden

Source: Hind, Hindoostan, or India. By L.S. de la Rochette. MDCCLXXXVIII. London, published by William Faden, Geographer to the King and to H.R.H. the Prince of Wales. 3d. edition with considerable improvements, June 1st, 1800. Wm. Palmer, sculp.

(1914) Richard Carnac Temple

Source: The Travels of Peter Mundy, in Europe and Asia, 1608-1667, Vol. II. Travels in Asia, 1628-1634. Ed. Sir Richard Carnac Temple. Hakluyt Society, Second Series, No. XXXV. London: 1914. pp 39.