Introduction

by Dr Ayesha Mukherjee

- Overview

- Contexts

- Content and approach

- Sources and searchability

- Languages and translation

- Genres

- Apparatus

- Blog

- Selected bibliography

3. Content and approach

The parallel chronologies of Indian and British famines and dearth, and patterns of interaction, suggest that the cultural zones of the two countries were not impermeable, nor were experiences and cultural meanings of economic and environmental crisis mutually exclusive. We have avoided using post-colonial paradigms to evaluate pre-colonial discourses, since this can create two linked problems. Focus on the impetus for power, dominance, and exploitation alone can marginalize the complex interplay of sympathy and cooperation, simultaneously operative in contexts of crisis. This, in turn, underplays the potential pre-colonial discourses of famine have to offer valuable insights for addressing issues of food security in the future. For example, users may find that early European travellers to India, many of whose narratives are contained in the database, showed greater vulnerability to famine and awareness of climatic, topographical, and environmental factors; they were sympathetic to local migrants with whom they travelled, and criticised the imperial policies of Mughal monarchs when these failed to adequately address, or aggravated, the crisis. A further search through the sources which describe riots and protests during famines in Britain might reveal similarities with popular criticisms of official measures that inadequately addressed (or caused) shortages.

The content, textual apparatus, structure, and search functions of the database are therefore designed to enable users to explore the comparative potential of the material. There is also a rich body of scholarly work on the socio-economic contexts and literature of early modern Britain and Mughal India, which have been consulted during this project and are selectively listed in the bibliography.

Drunk European seated on the ground (ca.1580-85). Attributed to Basawan. Freer and Sackler Gallery of Art, Washington. Accession no. F1953.60. (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

This album painting by Basawan, the Mughal court painter during Akbar’s reign, is a direct contrast to the artist’s other work, done in a similar style, depicting three famished entities – the literary figure Majnun, a horse, and a dog – held at the Indian Museum, Calcutta. Basawan was also known for adapting the techniques of Renaissance naturalism, especially Dürer. In this ironic and humorous portrait of excess, the European musician is depicted by merging European naturalist techniques with comic exaggeration of features such as the large belly, the skewed hat, or the enormous pillow to match the rotundity of the man himself.

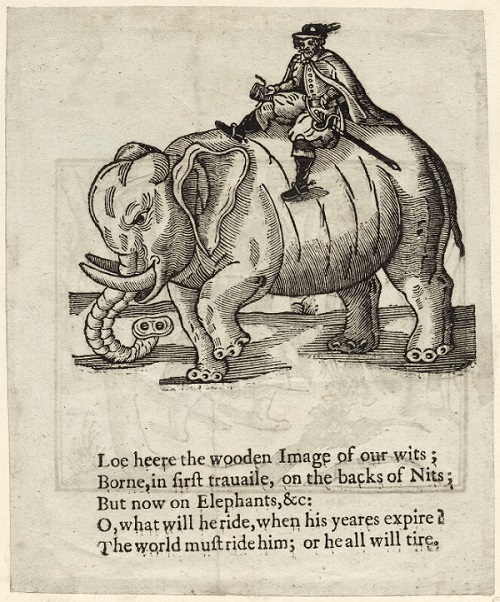

Thomas Coryate (17th century woodcut). Unknown Artist. National Portrait Gallery, London. Reference Collection, NPG D28033.

This portrait of Coryate appeared in the published account of his travels in India, Thomas Coriate traveller for the English wits, greeting: from the court of the Great Mogul, resident at the towne of Asmere, in easterne India (London: 1616), p.27. Coryate visited India out of curiosity rather than by imperial order, journeying over 3000 miles, mostly on foot. The elephant ride, possibly a brief courtly privilege, is an iconic image that he was determined to publish in his book.