Introduction

by Dr Ayesha Mukherjee

- Overview

- Contexts

- Content and approach

- Sources and searchability

- Languages and translation

- Genres

- Apparatus

- Blog

- Selected bibliography

4. Sources and searchability

Official discourses and documents predominantly used by historians to narrate the economic and political changes described above are undoubtedly important, and selections from such sources are part of our database. This project, however, uncovers the scope for studying famines in greater cultural detail, using a wider range of material, especially under-utilized vernacular sources, poetry, sermons, and other texts. Some of these may be well-known to scholars in the fields that usually study them, but not to scholars in other fields. Our purpose is to introduce scholars to comparable sources in different areas of study.

This material was collected by Mukherjee, who conducted research in 14 libraries and archives in India, UK, and Bangladesh, collating and checking printed sources with manuscripts, and making selections for the database. Many of these archives are underutilised, and while many libraries across the world have been generous with providing open access to their digitized sources, there were frequent issues with the legibility of digitised material, and their limited electronic searchability. The collaborating teams assisted with the selection process, transcribed and encoded the selections, and in many cases, translated them into English.

The combination of traditional scholarly processes and Digital Humanities in this project has thus introduced new ways of comparing and querying the sources, so that researchers can synchronically access material that is drawn from different archives, languages, and cultures. Based on relevance, some texts are fully transcribed, but in most cases, especially long texts (e.g., Mughal chronicles or English sermons), selections pertaining to famine, dearth, and related issues have been extracted.

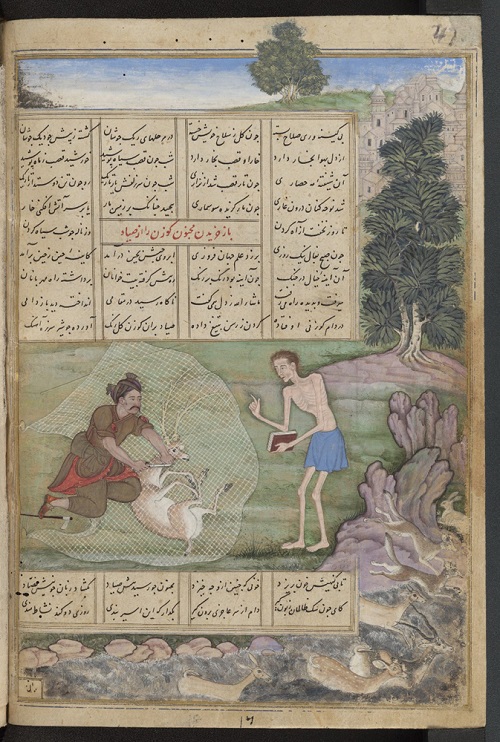

“Majnūn redeeming the deer from the huntsman” (1560-99). Unknown artist. Nizami Ganjavi, Lailā u Majnūn. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. MS.Pers.d.102, p.47. (CC by 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The painting appears in a manuscript owned by James Atkinson (1780-1852), surgeon and administrator in India, who translated Nizami’s poem composed in 1188. The manuscript text was copied in the 1560s, and the illustrations, added in the 1590s by some of the finest painters of Akbar’s court, depict scenes not often painted, such as Majnun redeeming the deer. The wandering, skeletal Majnun, having renounced earthly preoccupations, is shown to have sympathy with the natural and animal worlds. The scene, painted in the emerging Mughal (rather than Persian) style, is one where, in Atkinson’s translation, “Majnun, delighted, view’d his purchased prize, and in the gazelle’s sees his Laili’s eyes”.